Sin.

Now there is a word for you, and it is not just any word either. Can there be a more loaded word in the whole of the English language than this little three-letter word? Even though we don’t hear much about sin these days (Whatever Became of Sin? asks Karl Menninger, American psychiatrist, in his book of the same title, published in 1975), that sin actually exists is a plain perception of everyday reality that can be denied by none but the blind-as-a-bat few. It will of course depend on exactly what we understand by sin, no? After all, we must each have our point of view on one and the same truth, whoever we are, whatever that truth happens to be.

“The only sin is ugliness,” writes Herbert Read, “and if we believed this with all our being, all other activities of the human spirit could be left to take care of themselves.”

“The only sin,” avers Martha Graham, “is mediocrity.”

“There is no sin,” claims Oscar Wilde, “except stupidity.”

“The theologian considers sin mainly as an offence against God,” Thomas Aquinas tells us, “the moral philosopher as contrary to reasonableness.”

“For sin is just this,” states Martin Buber, “what man cannot by its very nature do with his whole being; it is possible to silence the conflict in the soul, but it is not possible to uproot it.”

“Original sin is that thing about man,” declares Reinhold Niebuhr, “which makes him capable of conceiving of his own perfection and incapable of achieving it.”

Apart from the exclusionary notions of the above first three, I would say we can accept without contradiction the truth of all of these statements. Even with these first three it should be possible to understand sin as at bottom ugliness or mediocrity (i.e., lack of creativity) or stupidity with all the subsequent particulars arising from the morass of any of these. I would wish only to add the following as one more important perspective:

Apart from the exclusionary notions of the above first three, I would say we can accept without contradiction the truth of all of these statements. Even with these first three it should be possible to understand sin as at bottom ugliness or mediocrity (i.e., lack of creativity) or stupidity with all the subsequent particulars arising from the morass of any of these. I would wish only to add the following as one more important perspective:

“Sin is whatever I may do that hinders spiritual progress, either in myself or in others, which either way in the end must come down to a refusal of the love of others.”

So what might be the result – in awareness of sin – to abandon sin? For Saint Paul, writing to the Christian community of Corinth (I Cor. 4:9b-13) who, in their lack of consciousness of sin, were claiming through the sins of complacency and pride an exalted spiritual status, apostles are exhibited by God

So what might be the result – in awareness of sin – to abandon sin? For Saint Paul, writing to the Christian community of Corinth (I Cor. 4:9b-13) who, in their lack of consciousness of sin, were claiming through the sins of complacency and pride an exalted spiritual status, apostles are exhibited by God

. . . as last of all, as though sentenced to death, because we have become a spectacle to the world, to angels and to mortals. We are fools for the sake of Christ, but you are wise in Christ. We are weak, but you are strong. You are held in honor, but we in disrepute. To the present hour we are hungry and thirsty, we are poorly clothed and beaten and homeless, and we grow weary from the work of our own hands. When reviled, we bless; when persecuted, we endure; when slandered, we speak kindly. We have become like the rubbish of the world, the dregs of all things, to this very day.

Not exactly a goal to aim for by the ambitious of this world, to be sure, yet there has been a whole category of saint whose ambition it is to become precisely just such a fool for Christ as the Apostle Paul so graphically describes. “Here comes the time,” proclaimed Anthony the Great (c. 251–356), “when people will behave like madmen, and if they see anybody who does not behave like that, they will rebel against him and say: ‘You are mad’, — because he is not like them.”

Not like them as in the words of Paul: “For the message of the cross is foolishness to those who are perishing, but to us who are being saved it is the power of God.” (1 Cor. 1:18) This singular ambition can be traced all the way back to the desert fathers and mothers, Isidora Barankis of Egypt (died c. 365), nun and saint, being among the first of a long line of holy fools appearing thenceforward through the many centuries. Living in an Egyptian convent, she veiled her head with an old dishrag, bringing contempt upon her from the other nuns. It was when the hermit Saint Pitirim visited the convent after the vision of an angel, who had told him to “find an elect vessel full of the grace of God . . . by the crown that shines above her head”, that this crown was all at once seen shimmering above Saint Isidora. In repentance falling to the feet of Pitirim, all in the monastery confessed and renounced their sinful attitude toward Isidora, who had pretended to be mad, having suffered countless insults and even beatings humbly. Isidora, unable to bear such honors and apologies, secretly left the convent after a few days to spend the rest of her life as a recluse in the desert.

Not like them as in the words of Paul: “For the message of the cross is foolishness to those who are perishing, but to us who are being saved it is the power of God.” (1 Cor. 1:18) This singular ambition can be traced all the way back to the desert fathers and mothers, Isidora Barankis of Egypt (died c. 365), nun and saint, being among the first of a long line of holy fools appearing thenceforward through the many centuries. Living in an Egyptian convent, she veiled her head with an old dishrag, bringing contempt upon her from the other nuns. It was when the hermit Saint Pitirim visited the convent after the vision of an angel, who had told him to “find an elect vessel full of the grace of God . . . by the crown that shines above her head”, that this crown was all at once seen shimmering above Saint Isidora. In repentance falling to the feet of Pitirim, all in the monastery confessed and renounced their sinful attitude toward Isidora, who had pretended to be mad, having suffered countless insults and even beatings humbly. Isidora, unable to bear such honors and apologies, secretly left the convent after a few days to spend the rest of her life as a recluse in the desert.

She who renounced sin, becoming by this a fool for Christ, brought to manifestation the hidden sin of the others. “Whoever says, ‘I am in the light,’ while hating a brother or sister, is still in the darkness. Whoever loves a brother or sister lives in the light, and in such a person there is no cause of stumbling. But whoever hates another believer is in the darkness, walks in the darkness, and does not know the way to go, because the darkness has brought on blindness.” (1 John 2:9-11)

In the Russian Orthodox Church, a holy fool (yurodivy), of which there are thirty-six officially recognized on the liturgical calendar, is one who acts intentionally foolish in the eyes of others. Often going around half-naked and homeless, such a one speaks in riddles, is believed to be clairvoyant and a prophet, is possibly disruptive at times, is sometimes so challenging as to seem downright immoral, there always being however a point to be made by such behavior. Either real or simulated, the madness of holy fools has been traditionally held to be divinely inspired, enabling these saints to voice truths the conventionally sane are unable to voice, usually in the guise of parables or indirect allusions: thus the status these saints traditionally have had in regard to the rich and powerful, their wisdom not being subject to worldly control.

Today in the Russian Orthodox Church the Blessed Nicholas of Pskov, Fool for Christ, is commemorated. It is said that in 1570 when, suspecting the inhabitants of treason, the Tsar Ivan the Terrible moved against the city of Pskov, he came, according to the chronicler, “with great fierceness, like a roaring lion, to tear apart innocent people and to shed much blood.” We have the following account of what followed from the Orthodox Church in America website:

Today in the Russian Orthodox Church the Blessed Nicholas of Pskov, Fool for Christ, is commemorated. It is said that in 1570 when, suspecting the inhabitants of treason, the Tsar Ivan the Terrible moved against the city of Pskov, he came, according to the chronicler, “with great fierceness, like a roaring lion, to tear apart innocent people and to shed much blood.” We have the following account of what followed from the Orthodox Church in America website:

On the first Saturday of Great Lent, the whole city prayed to be delivered from the Tsar’s wrath. Hearing the peal of the bell for Matins in Pskov, the Tsar’s heart was softened when he read the inscription on the fifteenth century wonderworking Liubyatov Tenderness Icon of the Mother of God (March 19) in the Monastery of St Nicholas (the Tsar’s army was at Lubyatov). “Be tender of heart,” he said to his soldiers. “Blunt your swords upon the stones, and let there be an end to killing.”

On the first Saturday of Great Lent, the whole city prayed to be delivered from the Tsar’s wrath. Hearing the peal of the bell for Matins in Pskov, the Tsar’s heart was softened when he read the inscription on the fifteenth century wonderworking Liubyatov Tenderness Icon of the Mother of God (March 19) in the Monastery of St Nicholas (the Tsar’s army was at Lubyatov). “Be tender of heart,” he said to his soldiers. “Blunt your swords upon the stones, and let there be an end to killing.”

All the inhabitants of Pskov came out upon the streets, and each family knelt at the gate of their house, bearing bread and salt to the meet the Tsar. On one of the streets Blessed Nicholas ran toward the Tsar astride a stick as though riding a horse, and cried out: “Ivanushko, Ivanushko, eat our bread and salt, and not Christian blood.” The Tsar gave orders to capture the holy fool, but he disappeared.

Though he had forbidden his men to kill, Ivan still intended to sack the city. The Tsar attended a  Molieben at the Trinity cathedral, and he venerated the relics of holy Prince Vsevolod-Gabriel (February 11), and expressed his wish to receive the blessing of the holy fool Nicholas. The saint instructed the Tsar “by many terrible sayings,” to stop the killing and not to plunder the holy churches of God. But Ivan did not heed him and gave orders to remove the bell from the Trinity cathedral. Then, as the saint prophesied, the Tsar’s finest horse fell dead.

Molieben at the Trinity cathedral, and he venerated the relics of holy Prince Vsevolod-Gabriel (February 11), and expressed his wish to receive the blessing of the holy fool Nicholas. The saint instructed the Tsar “by many terrible sayings,” to stop the killing and not to plunder the holy churches of God. But Ivan did not heed him and gave orders to remove the bell from the Trinity cathedral. Then, as the saint prophesied, the Tsar’s finest horse fell dead.

The blessed one invited the Tsar to visit his cell under the bell tower. When the Tsar arrived at the cell of the saint, he said, “Hush, come in and have a drink of water from us, there is no reason you should shun it.” Then the holy fool offered the Tsar a piece of raw meat. “I am a Christian and do not eat meat during Lent”, said Ivan to him. “But you drink human blood,” the saint replied. Frightened by the fulfillment of the saint’s prophecy and denounced for his wicked deeds, Ivan the Terrible ordered a stop to the looting and fled from the city.

The Oprichniki, witnessing this, wrote: “The mighty tyrant … departed beaten and shamed, driven off as though by an enemy. Thus did a worthless beggar terrify and drive off the Tsar with his multitude of a thousand soldiers.”

Blessed Nicholas died on February 28, 1576 and was buried in the Trinity Cathedral of the city he had saved. Such honors were granted only to the Pskov princes, and later on, to bishops.

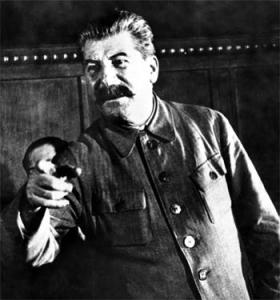

Practically everyone who takes the trouble to read up on Ivan the Terrible would agree, I am sure, that this despot qualifies as one of the world’s great and mighty sinners. Yet there he is fleeing the city at the words of that “worthless beggar”, Nicholas of Pskov, Fool for Christ. This however is to the Tsar Ivan’s credit, I think, just as the softening of his heart is to his credit in his encounter with the wonderworking Liubyatov Tenderness Icon of the Mother of God. Who can imagine Joseph Stalin in similar circumstances, either fleeing or softening? However rudimentary, however riddled with superstition his sense of sin, Ivan the Terrible seems to have retained that sense still, whereas Stalin, it appears, did not. Would anyone who says, “Gratitude is a sickness suffered by dogs” and “Death solves all

Practically everyone who takes the trouble to read up on Ivan the Terrible would agree, I am sure, that this despot qualifies as one of the world’s great and mighty sinners. Yet there he is fleeing the city at the words of that “worthless beggar”, Nicholas of Pskov, Fool for Christ. This however is to the Tsar Ivan’s credit, I think, just as the softening of his heart is to his credit in his encounter with the wonderworking Liubyatov Tenderness Icon of the Mother of God. Who can imagine Joseph Stalin in similar circumstances, either fleeing or softening? However rudimentary, however riddled with superstition his sense of sin, Ivan the Terrible seems to have retained that sense still, whereas Stalin, it appears, did not. Would anyone who says, “Gratitude is a sickness suffered by dogs” and “Death solves all  problems – no man, no problem” and means what he says, as he most certainly did – would any murderer, that is, of 30 to 50 million human beings – have any feeling of sin left in him? Not too bloody likely, and any holy fool getting close enough to say similar words to Papa Stalin would – who can doubt it – suffer a swift martyrdom, make no mistake.

problems – no man, no problem” and means what he says, as he most certainly did – would any murderer, that is, of 30 to 50 million human beings – have any feeling of sin left in him? Not too bloody likely, and any holy fool getting close enough to say similar words to Papa Stalin would – who can doubt it – suffer a swift martyrdom, make no mistake.

Even if the word sin has virtually disappeared from our vocabulary, we should by now see that a sense of sin remains nevertheless a prerequisite for spiritual progress. “Sin is a ‘weary word’, writes Bernard Murchland in his introduction to a book of essays entitled Sin (Macmillan, 1962) “but the reality it signifies is energetic and destructive. . . . Our age is as haunted by the presence of sin as any other—perhaps more so. . . . The problem of sin is the axial problem of human thought and no effort of man’s mind has any lasting importance that is not concerned with that problem.”

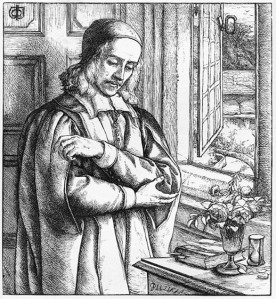

In other words, paradoxically, no effort of any man’s mind has any lasting importance unless it becomes first and above all an effort to make that very same mind, in its resolve to renounce sin, a fool for Christ. Yes, a fool for Christ to be sure — we are talking about the mind after all — but there is more than one way of accomplishing that sea-change. We can look to George Herbert (April 3, 1593 – March 1, 1633) as an example of another way, who as a saint on the Anglican liturgical calendar was commemorated yesterday.

Born into an artistic and wealthy family, receiving a good education which led to his holding prominent positions at Cambridge University and Parliament, he excelled in languages and music. Although he went to college with the intention of becoming a priest, his scholarship attracted the attention of King James I, with the end result of his serving in parliament for two years. But, at the urging of a friend, Herbert’s interest in being ordained was renewed. It was in 1630, in his mid-thirties, that he gave up all secular aims and took holy orders in the Church of England, spending the rest of his life as a rector of the little parish of Fugglestone St. Peter with Bemerton St. Andrew, near Salisbury. With his own money he had the churches repaired. Noted for unfailing care for his parishioners, he brought the sacraments to them when they were ill, provided food and clothing for them when in need, dying of tuberculosis before he reached forty. Thus he who looked to have a brilliant career laid out before him, turned off that road, only to go live in complete obscurity in a country village a whole world away from university, from court and parliament, from all that would serve normal human ambition.

Born into an artistic and wealthy family, receiving a good education which led to his holding prominent positions at Cambridge University and Parliament, he excelled in languages and music. Although he went to college with the intention of becoming a priest, his scholarship attracted the attention of King James I, with the end result of his serving in parliament for two years. But, at the urging of a friend, Herbert’s interest in being ordained was renewed. It was in 1630, in his mid-thirties, that he gave up all secular aims and took holy orders in the Church of England, spending the rest of his life as a rector of the little parish of Fugglestone St. Peter with Bemerton St. Andrew, near Salisbury. With his own money he had the churches repaired. Noted for unfailing care for his parishioners, he brought the sacraments to them when they were ill, provided food and clothing for them when in need, dying of tuberculosis before he reached forty. Thus he who looked to have a brilliant career laid out before him, turned off that road, only to go live in complete obscurity in a country village a whole world away from university, from court and parliament, from all that would serve normal human ambition.

But, as it happened, in addition to being a priest, he was also a poet, and a poet quite remarkable besides. On his deathbed he handed over all his poems to his friend Nicholas Ferrar, asking him to make them available to any poor soul who might stand in need of them. Otherwise, if that were not to be, his friend was to burn them. Henry Vaughn, another intimate friend, remarked of Herbert that he was “a most glorious saint and seer”, aware that the humble priest had written poetry nearly all his life.

But, as it happened, in addition to being a priest, he was also a poet, and a poet quite remarkable besides. On his deathbed he handed over all his poems to his friend Nicholas Ferrar, asking him to make them available to any poor soul who might stand in need of them. Otherwise, if that were not to be, his friend was to burn them. Henry Vaughn, another intimate friend, remarked of Herbert that he was “a most glorious saint and seer”, aware that the humble priest had written poetry nearly all his life.

In accordance with our contemplation upon the matter of sin, the following poem “Love” by George Herbert, widely anthologized in our day, well addresses what I think is an inevitable question concerning its dark reality in every human soul: the question being, if it is sin that separates us from God, and if sin is integral to our human nature, what honestly is anyone’s chance of ever having an authentic encounter with God?

LOVE bade me welcome; yet my soul drew back,

Guilty of dust and sin.

But quick-eyed Love, observing me grow slack

From my first entrance in,

From my first entrance in,

Drew nearer to me, sweetly questioning

If I lack’d anything.

‘A guest,’ I answer’d, ‘worthy to be here:’

Love said, ‘You shall be he.’

‘I, the unkind, ungrateful? Ah, my dear,

I cannot look on Thee.’

Love took my hand and smiling did reply,

‘Who made the eyes but I?’

‘Truth, Lord; but I have marr’d them: let my shame

Go where it doth deserve.’

‘And know you not,’ says Love, ‘Who bore the blame?’

‘My dear, then I will serve.’

‘You must sit down,’ says Love, ‘and taste my meat.’

‘You must sit down,’ says Love, ‘and taste my meat.’

So I did sit and eat.

If, because of sin, fools we must be, then for Christ’s sake let us resolve to be holy fools, whether of one kind or of the another. This proposition is ridiculously simple, for as Herbert affirms, “There is an hour wherein a man might be happy all his life, could he find it.” And we have found that hour, dear Reader, truly we have found it. If you doubt it, just ask that holy fool Saint Paul the Apostle.

Pax et Bonum,

Randall Scott